On the Feast of Mother Clara Pfaender, Foundress

TEXTS: Jeremiah 29:11-14

Excerpt from the Founding Constitution

John 12:20-26

INVOCATION: The prophet Isaiah retells a promise about the Word of the LORD, comparing it to

. . . the rain and the snow [that] come down from heaven, and do not return there until they have watered the earth, making it bring forth and sprout, giving seed to the sower and bread to the eater. So shall the word be that goes out from God’s mouth; it shall not return to God empty, but it shall accomplish that which God intends, and succeed in the thing for which God sent it. (Isaiah 55:10-11).

So may it be!

If you’ve been around here long enough, you’ve probably heard me give the readings, you’ve probably heard me sing a litle, you may have heard me present about the environment and Climate Change, and—if you go far enough back—you may have taken one of my classes on Visio Divina. But you haven’t heard me preach. There’s a first time for everything.

For those of you who don’t know me, I have been a Covenant Companion here since 2005. I’m a single gay man, divorced more than 20 years ago, and the father of one grown son. I grew up and raised my family in the Evangelical Protestant tradition, and 18 years ago, I started the catechism with Fr. Tom and was confirmed in this chapel. Some of you were probably here for that occasion.

Given this biography, such as it is, you might wonder why a non-vowed member of the community is tanding before you on the Feast of its foundress—and (hello!) a male member of the community, no less, and a convert at that. As a gay and divorced man, and as a recovering Bible-thumper, you might think I’m the least appropriate person to be doing this. And you wouldn’t be alone; for the past several weeks I have wondered the same thing. Melanie Teska promised me that this would be no problem.

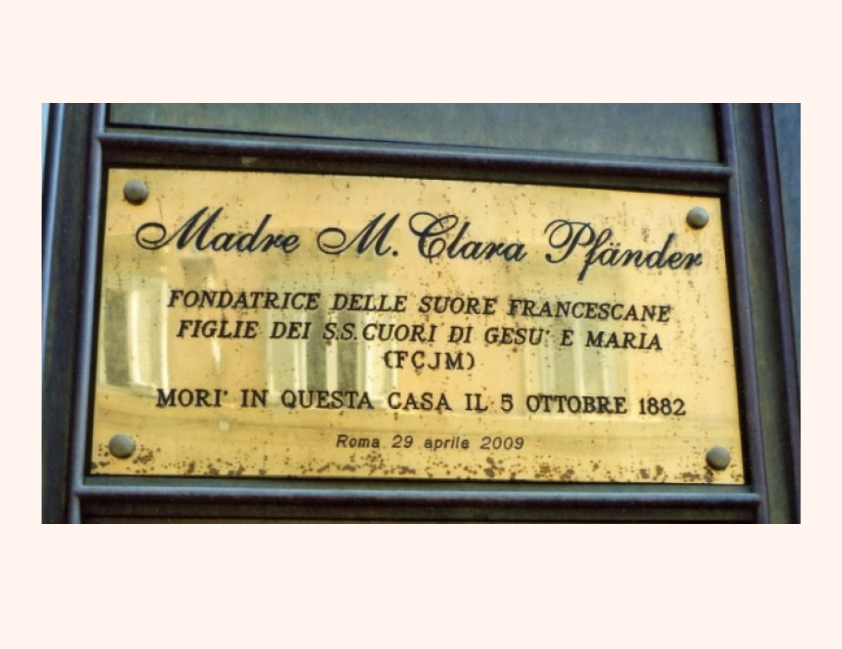

Nevertheless, I have a story to tell. And I hope you have ears to hear. Your worship order has an image [see below] of a brass plaque memorializing M. Clara’s passing in 1882. Etched in Italian, it says, “Mother M. Clara Pfaender, foundress of the Franciscan Sisters, Daughters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary (fcjm), died in this house on October 5, 1882.” That is, 142 years ago today.

By the way, let me thank our archivist, Kevin Korst, who promptly located this image for our service today when I couldn’t find it. Our Congregation placed this plaque in April 2009 near the entrance of Via Sistina 149 in Rome.

Via Sistina 149 is an old (1860) apartment building, typical for the area, with restaurants on the street level and a bed-and-breakfast, among other occupants, right in the heart of Rome, about 500 yards from the Trevi Fountain, and about 6 blocks from the Basilica of Mary Major.

I saw this plaque myself two years later. Remember that S. Glenna mentioned pilgrimages yesterday; in the summer of 2011 I was a participant in a Pace e Bene pilgrimage. Nine Sisters and Covenant Companions from Wheaton joined Sisters from Brazil, Germany, the Netherlands, and Indonesia for a two-week excursion, visiting many of places of significance to Franciscans. One interesting factoid about that trip: There were 30 Pace e Bene pilgrims that year, 29 women and me. One other factoid: We received instructions in advance about how to dress during the pilgrimage, since we would be at churches, shrines, and other meaningful sites. I decided to wear a white shirt and khaki pants every day, just to keep things simple. I brought a tie and a navy blazer for emergencies. You will see this “habit” in every picture taken during that trip.

The last two days of Pace e Bene were dedicated to M. Clara’s time in Rome, and S. Mary Lou took us to 149 Via Sistina to see this memorial. For me, it was the first of several notable experiences on perhaps the most memorable day of the entire trip.

Via Sistina 149 was one of three places where M. Clara stayed while in Rome, where she spent the last year and a half of her life, awaiting an audience with the Pope. She was seeking an audience with the Pope to restore her reputation. And therein lies a tale.

Many of you know the story better than I do: The 1870s were marked by the Kulturkampf, an overt, sustained conflict between German Empire, especially Prussia, and the Roman Catholic Church. In the interest of separating church and state, among other goals, newly unified Germany passed laws to aggressively reduce the influence of church officials in education and other civic affairs, especially in certain regions of the Empire. Having founded it in 1860, a little more than 10 years later M. Clara was shepherding her young congregation with growing pains of its own, just as the suppression of the church was ramping up.

In 1875, in the midst of this political oppression, Father Konrad Martin, Bishop of Paderborn, gave M. Clara emergency authority, in his absence, to do three things to serve her young congregation: First, to choose confessors for the sisters; secondly, to admit new sisters to the congregation; and, lastly to receive vows. Two of those emergency delegations were in direct violation of the civil restrictions at that time. Bishop Martin further required that this delegation, which we call “The Burning Seal,” remain secret to prevent further persecution by the civil authorities. Bishop Martin was later arrested, escaped and fled Germany, and died in exile in 1879.

When, in her prudent judgment, M. Clara found it necessary to invoke the Bishop’s delegation, she drew lots of consternation among those who witnessed it, especially the local priests, the church hierarchy, and even from the sisters in the congregation. And not without reason: the civil authority at that time could have dissolved the growing congregation completely for violating the law, and perhaps compromise the existence of other parishes and institutes. M. Clara was identified as a problem, and sanctioned for the actitions she took under The Burning Seal. In 1880, she was removed from leadership and rejected by her own sisters.

Political oppression is far too common in human affairs; those with power and resources use them to silence those who disagree, alienate those who are different, and punish those who oppose. Secrecy can also be oppressive; those who know something can maintain their advantage over those who don’t know it.

And secrecy invites problems of its own; it causes us to speculate for reasons and factors when a situation doesn’t comport with our understanding. We tend to fill in the gaps with our own guesses and assumptions, which are rarely accurate. Secrecy can be very costly.

What followed for M. Clara and her secret, much of which has been documented in exquisite detail, is a nightmarish mix of patriarchy, misinformation, misunderstanding, blame, betrayal, calumny, and capegoating. Does that sound familiar? It might, because Jeremiah prophesied in a similar context. Known as “The Weeping Prophet,” Jeremiah lived in the late 7th century, BCE, and brought unwelcome news to the kingdom of Judah about its idolatry, greed, injustice, and social decay. Like so many prophets, he was persecuted and exiled for bearing difficult news. He witnessed the siege and fall of Jerusalem and the beginning of the Babylonian captivity.

However, Jeremiah also prophesied the restoration of Jerusalem and the eventual return of those exiled. And we heard his hopeful refrain in the first reading:

For surely I know the plans I have for you . . . plans for your welfare and not for harm, to give you a future with hope. (29:11)

The Gospel we just heard has a similar context. In John’s telling, Jesus has just raised Lazarus of Bethany, and has entered Jerusalem for the last week of his life, drawing tremendous crowds who hope that he will deliver them from their Roman occupiers. Jesus is well aware of the covert opposition he faces and the likely outcome. And, to top it all off, some visiting foreigners want to know what Jesus is all about, too.

The religious leaders of the day are beside themselves about Jesus’ fame (and they want to arrest Lazarus, too, because the story of his miraculous return is adding more followers); they plot his death one week later. It’s a similar recipe of deceit, disinformation, betrayal, blame, manipulation of civil authority, owardice, calumny, and scapegoating.

Jesus talked freely about what he anticipated, and it troubled his disciples. I wonder if perhaps he used a metaphor to soften the news:

Very truly I tell you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains just a single grain; but if it dies, it bears much fruit. (12:24).

And like Jeremiah, Jesus words offer hope to those who realize how grave the next few days might be:

Whoever serves me must follow me, and where I am, there will my servant be also. Whoever serves me, the Father will honor. (12:26).

Which brings us to M. Clara in Rome. Except for another sister who was a helper, she was on her own. She was without the congregation of sisters she had nurtured for the past 20-odd years, and without the bishop who provided ecclesial support. I speculate that Rome in general was not a friendly place for a German religious sister who had lost her life’s ministry. M. Clara was without resources, so much so that she had debts for rent, food, and pharmacy at the time of her death. I cannot imagine a more difficult, iscouraging, and fearsome predicament. Can there be any better example of Franciscan poverty and minority? Amid all these circumstance M. Clara herself expressed her faith and hope, writing:

The sun remains above and will again bring light into this darkness.

This just takes my breath away.

Let me return to the pilgrimage in 2011. After seeing Via Sistina 149 that morning, our next stop was the church of San Carlino of the Four Fountains, just a block away. We learned that M. Clara spent time there regularly, participating in that community’s prayer, worship, and sacrament. It occurred to me as we ntered San Carlino that our group was quite a collection of pilgrims.

By the time M. Clara died, her congregation had houses in Germany, France (since 1871), the Netherlands (since 1874), and the first new province here—in St. Louis—starting in 1872. M. Clara would have had no knowledge thereafter of the congregation’s presence elsewhere in the world, including Indonesia, Brazil, Romania, and Malawi. If M. Clara was the grain of wheat in today’s Gospel, we are some of the fruit that came from its death. The seed bears much fruit, indeed!

We had Mass at San Carlino. The presider spoke Italian and the Indonesian sisters sang the Mass parts. The acoustics were wonderful, and although almost no English was spoken, I felt very much a part of the Mass. Before the service ended, I had an unusual experience: I had a profound sense of M. Clara’s resence with us in the chapel—I envisioned her in the balcony behind us and looking down at this group with a mix of wonderment, thanksgiving, and delight.

Now, I am a scientist by training and rational by nature; I am not given to imagination or ecstasy. I am firmly planted in the material world; I get my inspiration from occasional glimpses of the spiritual plane. I am usually surprised by my intuitive experiences; I find them to be unfamiliar, and even a bit fearsome. But M. Clara’s presence seemed quite real to me, even if unseen. So, just to regain my bearings, I entioned my experience to Jeanne Connolly on the bus ride afterwards, and she told me she felt the same thing. Fancy that! I thought maybe after two weeks with 29 women (or wearing the same set of white shirts and khaki pants every day), my gears were starting to slip!

Let me conclude by saying that the calamity experienced by M. Clara leading up to her time in Rome is not unexplainable; not to minimize it in any way, but it is what happens when we give our collective dark sides a foothold. Jeremiah’s misery when he prophesied about the downfall of Jerusalem was exceptionally difficult to bear, both by the prophet and the audience; nobody likes bad news, and we often punish the one who brings it. A secular social or political scientist might look at Jesus’ last week in Jerusalem and say that when religious leaders collude with civil authorities to achieve their goals, trouble can be expected.

If there is one theme or one collective lesson from our readings today about Jeremiah, M. Clara, and Jesus, I would take it from Genesis 1, “Let there be light.” We frequently refer to Jesus as the “Light of the World;” John tells us that in Jesus was life and the light in all people (1:4). Figuratively, light can expose our shortcomings and errors so that we can take corrective steps. We call that conversion in the Franciscan parlance. Light, as a metaphor for honesty and transparency, can keep a secret from becoming a conspiracy and prevent an assumption from becoming a false legend. Physically, light is the energy source by which a dormant grain of wheat germinates, grows, and multiplies to become fruit and sustenance. And for M. Clara—whose name is a descriptor of light, meaning bright or clear—light was a symbol of hope, knowing that darkness of her circumstances was temporary and would resolve because the sun still shines above.

Let us walk in the Light; let us be in the Light; let us be the Light.

Pace e bene to all. Thank you!

Written by: Seth Dibblee (Covenant Companion)